Рекомендации по количественному анализу оползневых рисков. Часть 10

ВАН ВЕСТЕН К.

Факультет геоинформатики и наблюдений за Землей Университета Твенте, г. Энсхеде, Нидерланды

ФРАТТИНИ П.

Факультет наук о Земле и окружающей среде Миланского университета Бикокка, г. Милан, Италия

КАШИНИ Л.

Факультет гражданского строительства Университета Салерно, г. Салерно, Италия

МАЛЕ Ж.-П.

Национальный центр научных исследований при Страсбургском институте физики Земли, г. Страсбург, Франция

ФОТОПУЛУ С.

Отделение по исследованиям геотехнической сейсмостойкости и динамики грунтов факультета гражданского строительства Университета Аристотеля в Салониках, г. Салоники, Греция

КАТАНИ Ф.

Факультет наук о Земле Флорентийского университета, г. Флоренция, Италия

ВАН ДЕН ЭКХАУТ М.

Институт окружающей среды и устойчивого развития Объединенного исследовательского центра Европейской комиссии, г. Испра, Италия

МАВРОУЛИ О.

Факультет геотехники и наук о Земле Технического университета Каталонии, г. Барселона, Испания

АЛЬЯРДИ Ф.

Факультет наук о Земле и окружающей среде Миланского университета Бикокка, г. Милан, Италия

ПИТИЛАКИС К.

Отделение по исследованиям геотехнической сейсмостойкости и динамики грунтов факультета гражданского строительства Университета Аристотеля в Салониках, г. Салоники, Греция

ВИНТЕР М.Г.

Лаборатория транспортных исследований (TRL), г. Эдинбург, Великобритания

ПАСТОР М.

Институт инженеров путей сообщения Мадридского политехнического университета, г. Мадрид, Испания

ФЕРЛИЗИ С.

Факультет гражданского строительства Университета Салерно, г. Салерно, Италия

ТОФАНИ В.

Факультет наук о Земле Флорентийского университета, г. Флоренция, Италия

ЭРВАС Й.

Институт окружающей среды и устойчивого развития Объединенного исследовательского центра Европейской комиссии, г. Испра, Италия

СМИТ Дж.Т.

Компания Golder Associates (ранее – TRL), г. Бурн-Энд, графство Бакингемшир, Великобритания

Предлагаем вниманию читателей немного сокращенный адаптированный перевод обзорной статьи итальянских, испанских, греческих, британских, голландских и французских исследователей «Рекомендации по количественному анализу оползневых рисков» (Corominas et al., 2014). Она была опубликована в 2014 году в рецензируемом научном журнале Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment («Бюллетень по инженерной геологии и окружающей среде»), который выпускается издательством Springer Science+Business Media от имени Международной ассоциации инженерной геологии и окружающей среды. Указанная работа находится в открытом доступе на сайте ResearchGate по лицензии CC BY 2.0 (предыдущей версии CC BY 3.0 и CC BY 4.0), которая позволяет распространять, переводить, адаптировать и дополнять ее при условии указания типов изменений и ссылки на первоисточник. В нашем случае полная ссылка на источник для перевода (Corominas et al., 2014) приведена в конце.

Сегодня приводим раздел, посвященный оценке прогностической надежности карт оползневого зонирования.

Напомним, что в предыдущих и настоящей частях нумерация формул, рисунков и таблиц сквозная, а список литературы увеличивается по мере публикации продолжений.

Перевод статьи выполнен при поддержке ГК «ПЕТРОМОДЕЛИНГ» и Алексея Бершова.

ОЦЕНКА ЭФФЕКТИВНОСТИ КАРТ ОПОЛЗНЕВОГО ЗОНИРОВАНИЯ

Оценка неопределенностей, ошибкоустойчивости (робастности – robustness) и достоверности карты оползневого зонирования является сложной задачей.

Поскольку карты предрасположенности территорий к оползням, оползневых опасностей и рисков прогнозируют будущие события, наилучшим методом оценки было бы «подождать и посмотреть», проверить эффективность зонирования на основе событий, которые произошли после того, как были составлены карты. Однако это непрактичное решение, несмотря на то что последующие события могут обеспечить качественную степень уверенности для пользователей карт при условии, что понятны ограничения рассматриваемого периода времени, который неизбежно очень короток.

Проверка эффективности моделей является многокритериальной задачей, охватывающей:

1) адекватность (концептуальную и математическую) модели при описании системы;

2) ошибкоустойчивость (робастность) модели при небольших изменениях во входных данных (например, чувствительность к данным);

3) точность модели при прогнозировании данных [347, 348].

На практике эффективность модели оценивается с использованием данных инвентаризации оползней за определенный период времени и путем проверки результата с помощью другой инвентаризации за более поздний период. Однако сами инвентаризационные оползневые карты могут характеризоваться высокими уровенями неопределенности [52, 349].

Другой способ оценки эффективности модели – сравнение карт одной и той же территории, составленных независимо разными командами, хотя это оказалось довольно сложным [56, 350].

Чтобы охарактеризовать прогностическую эффективность карты зонирования, результаты инвентаризации оползней должны быть разделены на две группы (одна из которых используется для создания карты, а вторая – для анализа ее точности). Это можно сделать, используя случайную выборку оползней или применяя две карты инвентаризации, различающиеся по времени составления. Хорошее представление о прогностической точности также может дать сравнение карт зонирования, созданных разными методами.

В этом разделе представлен обзор методов, которые можно использовать для оценки эффективности карт предрасположенности территорий к оползням и карт оползневой опасности. Термин «эффективность» (performance) здесь применяется для отражения того, насколько правильно карты зонирования проводят различия между территориями, потенциально предрасположенными и не предрасположенными к возникновению оползней.

Неопределенности и ошибкоустойчивость (робастность) карт оползневого зонирования

Природа неопределенностей и тенденция к использованию более сложных моделей (например, путем перехода от эвристических к статистическим и основанным на процессах моделям) обусловливают необходимость в усовершенствованных инструментах идентификации и оценки моделей [351, 352] для доказательства того, что повышенная сложность действительно обеспечивает более хорошие результаты моделирования.

Для оценки оползневых моделей обычно учитываются алеаторные (связанные с внутренними свойствами системы – со случайным характером изучаемых процессов и явлений) и эпистемические (связанные с недостатком знаний или данных) неопределенности. Различия в интерпретации данных специалистами, участвующими в зонировании, относятся к эпистемическим неопределенностям.

Термин «ошибкоустойчивость» («робастнсть» – robustness) относится к изменению точности классификации из-за пертурбаций (нарушений, изменений) в процессе моделирования [353]. Анализ ошибкоустойчивости часто фокусируется только на нарушениях в работе модели из-за ошибок во входных параметрах [354]. В этом контексте термин «чувствительность» (sensitivity) [355] используется для идентификации ключевых неопределенных параметров, которые больше всего влияют на неопределенность выходных данных (для глобального анализа чувствительности), и для выделения параметров, которые оказывают наибольшее влияние на сами выходные данные, но не на их неопределенность (для локального анализа чувствительности).

Для оценки качества зонирования оползней можно рассмотреть использование количественных методов, основанных на дисперсии, для анализа глобальной чувствительности (например, для исследования влияния масштаба и формы распределения параметров) и применение графических методов для анализа локальной чувствительности [104]. Для внесения изменений в различные входные параметры используются вероятностные методы, основанные на теории моментов, поскольку они позволяют получать результаты в виде математических функций, а не уникальных значений [356]. Такие подходы дают возможность получать выходные данные на основе нескольких теоретических наборов входных данных и выводить доверительные интервалы, охватывающие эти обратные пути.

Авторами работ [289, 357–359] был выполнен анализ чувствительности входных параметров при оценке качества оползневого зонирования в детальном (сайт-специфическом) и локальном масштабах. В региональном масштабе анализ чувствительности возможен как для многомерных статистических моделей, так и для моделей процессов. Связанные гидрологические модели и модели устойчивости склонов, которые применяют метод «бутстреп» (bootstrap, bootstrapping – компьютерный метод, основанный на многократной генерации выборок методом Монте-Карло на базе имеющейся выборки и позволяющий оценивать статистические характеристики для сложных моделей. – Ред.), показывают, что физическое моделирование, основанное на средних значениях, не всегда может быть практичным [360]. В статьях [90, 104, 361] представлены другие примеры. В отношении многомерных статистических моделей только несколько статей посвящено оценке ошибкоучтойчивости (робастности) путем создания ансамблей моделей, откалиброванных для разных выборок оползней из одного и того же инвентаризационного набора [56, 362, 363] или путем калибровки моделей для разных инвентаризаций оползней для одного и того же региона [364]. В нескольких работах изучалось влияние разных классификаций независимых переменных, полученных по литологическим, почвенным картам или картам почвенно-растительного покрова [365]. А, например, авторы статьи [354] определили показатель робастности (ошибкоустойчивости), отражающий чувствительность к изменениям в наборе данных независимых (предикторных) переменных.

Точность карт зонирования

Ни одна из представленных в литературе методик оценки точности моделей оползневого зонирования не учитывает экономические издержки из-за неправильной классификации, которые становятся важными, когда зонирование применяется на практике для планирования использования земель. Это является существенным ограничением для анализа предрасположенности территорий к оползням, поскольку расходы из-за неправильной классификации варьируют в зависимости от типов ошибок. Последние могут быть следующими.

1. Ошибка типа I (ошибочно положительная классификация) – когда реальная территориальная единица без оползней классифицируется в модели как неустойчивая (есть или могут быть оползни) и, следовательно, имеющая ограничения в использовании и экономическом развитии. Следовательно, стоимость потерь из-за ошибочно положительной классификации соответствует потере экономической ценности таких территориальных единиц. Эта стоимость различна для разных единиц, поскольку является функцией экологических и социально-экономических характеристик.

2. Ошибка типа II (ошибочно отрицательная классификация) – когда реальная территориальная единица с оползнями классифицируется в модели как устойчивая (нет или не может быть оползней) и, следовательно, может использоваться без ограничений. Стоимость потерь из-за ошибочно отрицательной классификации соотвествует потере объектов, которые могут быть затронуты оползнями в пределах таких территориальных единиц.

В моделях оползневого зонирования издержки, связанные с ошибками типа II, обычно намного больше, чем затраты, связанные с ошибками типа I. Например, размещение такого общественного объекта, как здание школы, на территориальной единице, которая ошибочно определена как устойчивая (то есть сделана ошибка типа II), может привести к очень большим социальным потерям и экономическим затратам.

Далее представлены различные методы оценки эффективности оползневых моделей.

Статистические характеристики точности, зависящие от порогового значения

Точность оценивается путем анализа соответствия между выходными данными модели и результатами наблюдений. Поскольку результаты наблюдений говорят о наличии или отсутствии оползней в пределах определенной территориальной единицы, более простой метод оценки точности модели заключается в сравнении этих данных с двоичной классификацией предрасположенности территории к оползням на устойчивые и неустойчивые единицы. Такая классификация требует порогового (cutoff) значения предрасположенности, которое делит зоны на устойчивые (с предрасположенностью меньше пороговой) и неустойчивые (с предрасположенностью больше пороговой).

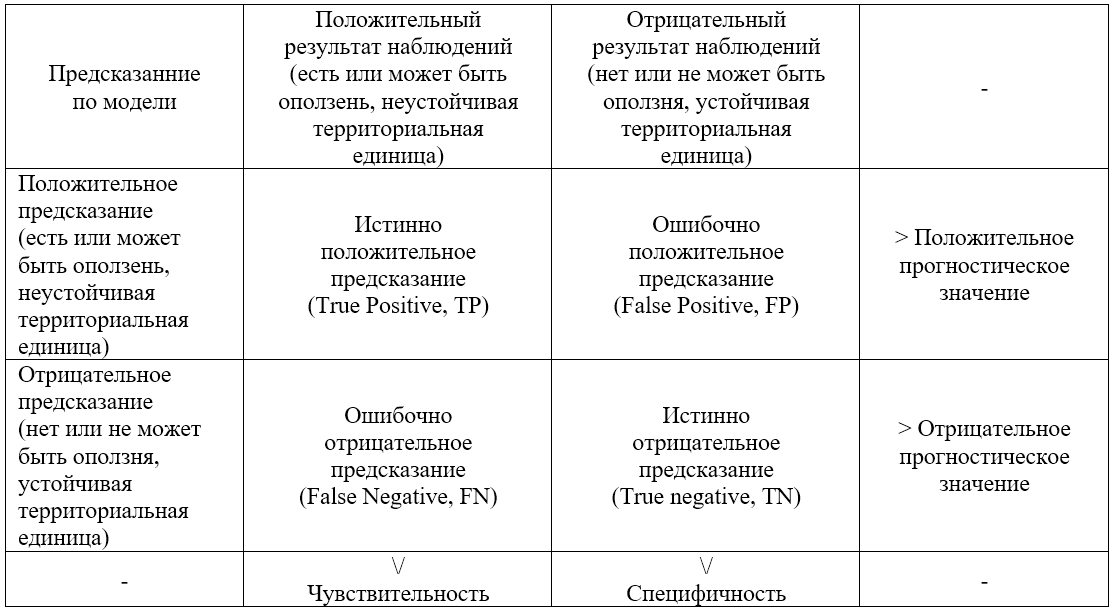

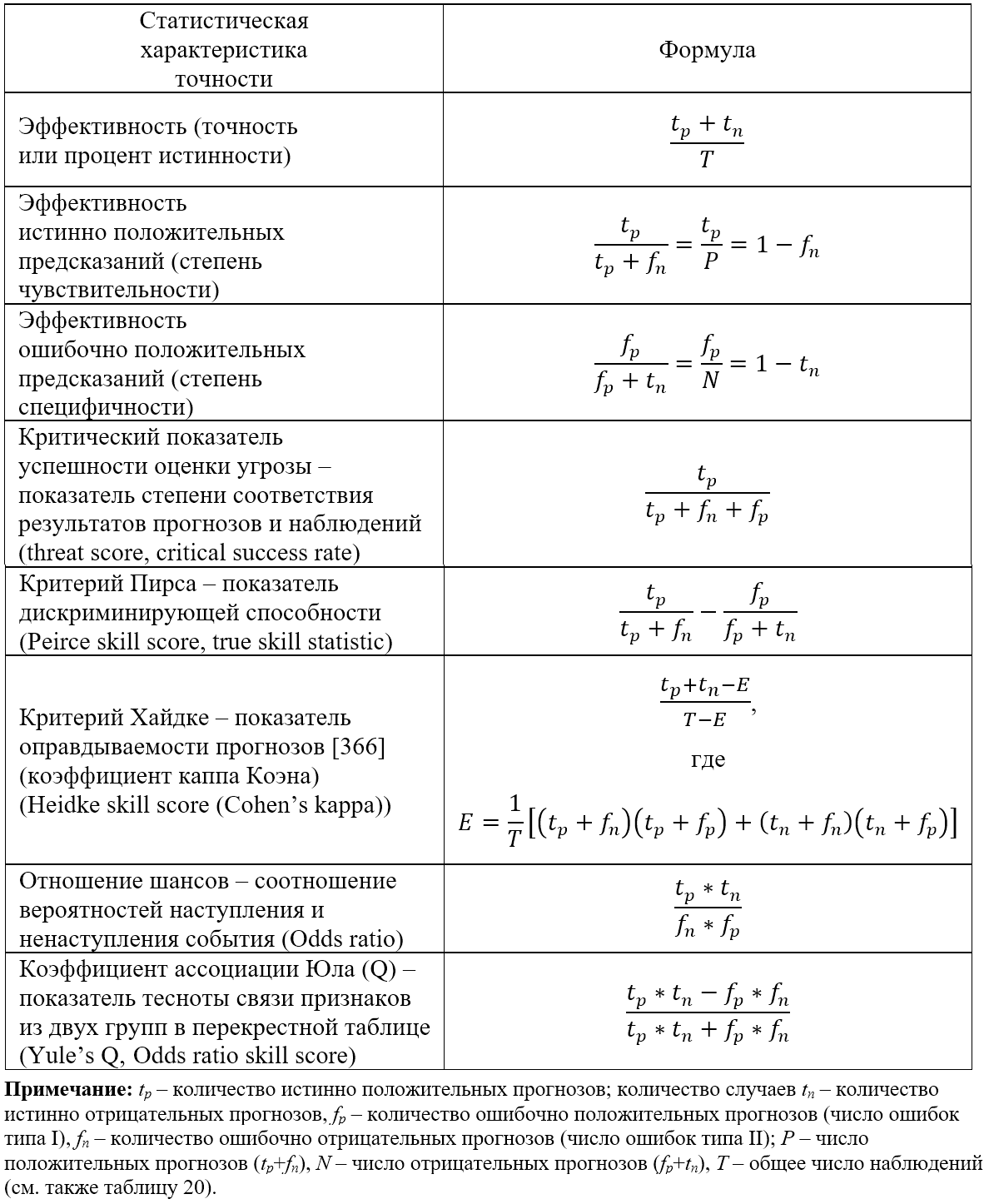

Сопоставление результатов наблюдений и модельных данных после их переклассификации на эти два класса представляют в виде таблиц сопряженности признаков (contingency tables ) (таблица 20). Статистические характеристики точности оценивают эффективность модели путем объединения правильно (истинно) и неправильно (ошибочно) классифицированных положительных и отрицательных по оползневой опасности случаев (таблица 21).

Таблица 20. Таблица сопряженности, используемая для оценки эффективности предсказаний по модели оползневого зонирования

Таблица 21. Обычно используемые статистические характеристики точности

Эффективность, которая выражается через процент случаев, правильно классифицированных моделью, недостоверна, поскольку на ее оценку сильно влияет наиболее распространенный класс (обычно «устойчивая единица площади»), и она не является объективной (например, получается одинаковая оценка для разных типов неквалифицированно выполненных классификаций). Это необходимо учитывать.

Истинно положительный (True Positive, TP) и ошибочно положительный (False Positive, FP) показатели – недостаточные статистические характеристики эффективности модели, поскольку они игнорируют ошибочно положительные и ошибочно отрицательные результаты соответственно. Они не являются объективными и полезны только при использовании в сочетании с чем-то еще (например, с «кривыми ошибок оценки», то есть ROC-кривыми, отражающими зависимость «чувствительность – частота ошибочно положительных заключений» и показывающими прогностическую ценность модели).

Показатель успешности оценки угрозы (threat score) [367] показывает долю наблюдаемых и/или классифицированных событий, которые были предсказаны правильно. Этот показатель не различает источники ошибок классификации. Более того, он зависит от частоты событий (поэтому более плохие оценки точности получаются для более редких событий, то есть обычно для более крупных оползней), поскольку некоторые истинно положительные предсказания могут получаться исключительно из-за случайности.

В качестве альтернативы можно использовать критерий Пирса (Peirce skill score), являющийся показателем дискриминирующей способности [368], или отношение шансов (odds ratio), то есть соотношение вероятностей наступления и ненаступления события [369].

Статистика точности требует разделения классифицированных объектов на несколько классов путем определения конкретных значений показателя предрасположенности территории к оползням, которые называются пороговыми (cutoff). Для статистических моделей существует статистически значимая пороговая вероятность (p[cutoff]), равная 0,5. Когда группы устойчивых и неустойчивых единиц площади равны по размеру и приближаются к нормальному распределению, это значение максимизирует количество правильно предсказанных устойчивых и неустойчивых единиц. Однако порог, используемый для определения классов предрасположенности, выбирается произвольно и, если не принят стоимостный критерий [370], зависит от цели карты, количества классов и типа используемого подхода к моделированию.

Первое решение этой проблемы состоит в оценке эффективности модели в широком диапазоне пороговых значений с использованием независимых от порога критериев эффективности.

Другой вариант состоит в поиске оптимального порогового значения путем минимизации стоимости.

Статистические показатели точности, не зависящие от порогового значения: кривые ROC и SR

Наиболее часто используемые методы оценки эффективности моделей зонирования оползней, не зависящие от пороговых значений, – «кривые ошибок оценки» (кривые ROC – Receiver Operating Characteristic) и «кривые успешности оценки» (кривые SR – Success Ratio, Success Ratio).

ROC-анализ в свое время был разработан для оценки эффективности радиолокационных приемников при обнаружении целей, но с тех пор он был принят в различных научных областях [371, 372]. Площадь под ROC-кривой (area under curve, AUC) может использоваться как показатель общего качества модели [373]: чем больше эта площадь, тем лучше эффективность модели для всего диапазона возможных пороговых значений. Точки на ROC-кривой соответствуют координатам (FP, TP), полученным из различных таблиц сопряженности, созданных путем применения разных пороговых значений (рис. 4, а). Точки, расположенные ближе к верхнему правому углу, соответствуют более низким порогам. Из двух ROC-кривых лучше та, которая расположена ближе к верхнему левому углу. Диапазон значений, для которых ROC-кривая лучше тривиальной модели (например, модели, классифицирующей объекты случайным образом и представленной в пространстве ROC прямой линией, соединяющей нижний левый и верхний правый углы; например, линия «1 – 1» на рисунке 4, а), определяется как рабочий диапазон. Когда точность модели оценивается с использованием данных, которые не применялись при разработке модели, модель является хорошей, если ROC-кривые для наборов оценочных и производственных данных расположены в ней близко друг к другу, а значения площади под кривой больше 0,7 (умеренная точность) или даже больше 0,9 (высокая точность) [374].

![Рис. 4. Примеры ROC-кривой (a) и SR-кривой (б) (по [56])](/images/dynamic/img54596.jpg)

При построении SR-кривых [375, 376] для оценок оползневого зонирования (рис. 4, б) по оси Y обычно откладывается процент суммарной площади (или количество) правильно классифицированных оползней. В случае ячеек сетки, где оползни соответствуют отдельным ячейкам и все единицы площади одинаковы, оси Y соответствуют истинно положительные (TP) результаты (аналогично пространству ROC), а оси X соответствует число единиц, классифицированных как положительные.

Стоимостные кривые

При оценке эффективности модели с помощью ROC-кривых можно учесть издержки в случае неправильной классификации, используя дополнительную процедуру [370]. Но получаемые при этом результаты трудно визуализировать и оценивать.

Стоимостные кривые [377] показывают нормализованную ожидаемую стоимость как функцию зависимости «вероятность – стоимость» (рис. 5), где ожидаемые издержки нормализованы по отношению к максимальным ожидаемым издержкам, которые возникают, когда все случаи классифицированы ошибочно (например, когда и FP, и FN равны единице). Максимальная нормализованная стоимость равна единице, а минимальная – нулю.

![Рис. 5. Пример получения стоимостной кривой. Каждая прямая линия соответствует точке на ROC-кривой. Например, красная штриховая иния соответствует точке с чувствительностью (TP), равной 0,91, и разности «1 – специфичность» (FP), равной 0,43 [378]](/images/dynamic/img54597.jpg)

Таким образом, единственная модель классификации, которая представляла бы собой единственную точку с координатами (FP, TP) в пространстве ROC, соответствует прямой линии в представлении стоимостной кривой (см. рис. 5). Чем ниже стоимостная кривая, тем лучше точность модели, а разница между двумя моделями заключается просто в расстоянии по вертикали между соответствующими им кривыми.

Для получения стоимостных кривых необходимо определить значение функции «вероятность – стоимость», которая зависит как от априорной вероятности, так и от издержек в случае неправильной классификации. Для моделей оползневого зонирования при учете неопределенности в наблюдаемом распределении совокупности оползней, разумным выбором является условие равновероятности [378].

Издержки в случае ошибочной классификации зависят от участка и значительно различаются в пределах изучаемой территории. Строгий анализ мог бы позволить выполнить их независимую оценку для каждой территориальной единицы и оценить общие издержки, суммируя затраты, возникающие в результате принятия каждой модели. Это потребует вклада администраторов и политиков из местных (муниципальных) и национальных органов власти.

Чтобы оценить среднюю стоимость для ошибочно отрицательных и ошибочно положительных прогнозов, можно использовать карту землепользования для расчета как площади, занимаемой объектами, потенциально подверженными риску (например, вносящими вклад в стоимость ошибочно отрицательных прогнозов), так и площади, потенциально пригодной для застройки (например, вносящей вклад в стоимость ошибочно положительных прогнозов) [378].

По этой причине карты прогнозируемой предрасположенности территорий к оползням должны быть тщательно проанализированы и критически рассмотрены перед обнародованием результатов. «Настройка» статистических методов и независимая валидация результатов уже признаны совершенно необходимыми этапами при любом исследовании природных опасностей для оценки точности и прогностической способности модели. Валидация может также позволить установить степень уверенности в модели и сравнить результаты, получаемые с помощью разных моделей. По этой причине также должна быть проверена пространственная согласованность карт подверженности территории к оползням, полученных с помощью разных моделей, особенно если эти модели характеризуются схожей прогностической способностью.

Ограничения на использование статистических характеристик точности

Применение каждого статистического показателя надежно только при определенных условиях (например, при редких или при частых событиях). Их следует оценивать в каждом конкретном случае, чтобы выбрать наиболее подходящий метод [369]. Это – ограничение на общее применение статистических характеристик для оценок качества оползневого зонирования.

Для статистических моделей простым и научно правильным является использование показателей точности, зависящих от порогового значения, поскольку оно статистически значимо. Это верно, только если принимаются равные априорные вероятности и равные издержки в случае ошибочной классификации – условия, которые обычно нарушаются в оползневых моделях. Для других видов моделей зонирования (эвристических, физически обоснованных) нет теоретических оснований для выбора определенного порогового значения, поэтому применение статистических показателей точности не годится.

Оценка эффективности карт оползневого зонирования с не зависящими от порогового значения критериями имеет то преимущество, что априорное пороговое значение не требуется и эффективность может быть оценена для всего диапазона порогов. Кривые ROC и SR дают разные результаты, поскольку ROC-кривая основывается на анализе классификации статистических единиц и описывает способность статистической модели различать два класса объектов, в то время как SR-кривая основывается на анализе пространственного соответствия между фактическими оползнями и картами зонирования и, таким образом, учитывает площади как оползней, так и территориальных единиц, а не только количество единиц, правильно или неправильно классифицированных.

SR-кривые связаны с некоторыми теоретическими проблемами, когда они применяются к моделям с ячейками сетки. Количество истинно положительных прогнозов фактически вносит вклад в значения, отложенные как по оси X, так и по оси Y. Увеличение числа истинно положительных прогнозов вызывает сдвиг кривой вверх (в сторону более хорошей эффективности) и вправо (в сторону более плохой эффективности). В некоторых случаях сдвиг вправо может происходить быстрее, чем вверх, вызывая кажущуюся потерю эффективности при увеличении количества истинно положительных прогнозов, а такая оценка эффективности явно обманчива. Более того, SR-кривая чувствительна к начальным соотношениям количеств положительных и отрицательных прогнозов. Следовательно, применение SR-кривых к территориям с низкой степенью опасности (например, с ровным рельефом лишь с небольшими крутыми участками) всегда даст более хорошие результаты, чем их использование для территорий с высокой степенью опасности (например, для горных долин с крутыми склонами), даже если качество классификации абсолютно одинаково.

Важным ограничением является то, что вышеупомянутые статистические показатели не являются пространственно явнымии и, соответственно, схожие формы кривых ROC и SR могут отражать разные пространственные случаи прогнозируемых устойчивых и неустойчивых территориальных единиц [379].

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

В этой статье были рассмотрены ключевые компоненты количественного анализа оползневых рисков (КолАР), который позволяет ученым и инженерам объективно и воспроизводимо оценивать риски и сравнивать результаты, полученные в разных местах (участках, регионах и т.д.). Важно понимать, что оценки рисков – это это всего лишь оценки. Ограничения на доступную информацию и использование чисел могут таить существенные потенциальные ошибки. В этом отношении результаты КолАР не обязательно являются более точными, чем качественные оценки, поскольку, например, вероятность может рассчитываться на основе личных суждений. Однако КолАР облегчает общение между специалистами в области наук о Земле, землевладельцами и лицами, принимающими решения.

Были представлены рекомендуемые методики количественного анализа оползневой опасности, уязвимости и риска в разных масштабах (детальном, локальном, региональном и национальном), а также методы верификации и валидации результатов. Рассмотренные методики сфокусированы на оценке вероятностей возникновения различных типов оползней с определенными характеристиками.

Также рассмотрены: методы определения пространственного распределения интенсивности оползней, объекты риска, оценка потенциальной степени ущерба, количественная оценка уязвимости объектов риска, а также КолАР.

Статья предназначена для ученых, инженеров-практиков, геологов и других специалистов по оползням.

-

Авторы выражают благодарность за поддержку проекта SafeLand (по грантовому соглашению 226479), финансируемого Европейской комиссией в рамках ее Седьмой рамочной программы.

Перевод статьи выполнен при поддержке ГК «ПЕТРОМОДЕЛИНГ» и Алексея Бершова.

ИСТОЧНИК ДЛЯ ПЕРЕВОДА

Corominas J., Van Westen C., Frattini P., Cascini L., Malet J.-P., Fotopoulou S., Catani F., Van Den Eeckhaut M., Mavrouli O., Agliardi F., Pitilakis K., Winter M.G., Pastor M., Ferlisi S., Tofani V., Hervas J., Smith J.T. Recommendations for the quantitative analysis of landslide risk // Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment. 2014. Vol. 73. № 2. P. 209–263. DOI:10.1007/s10064-013-0538-8. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259032330_Recommendations_for_the_quantitative_analysis_of_landslide_risk.

СПИСОК ЛИТЕРАТУРЫ, ИСПОЛЬЗОВАННОЙ АВТОРАМИ ПЕРЕВЕДЕННОЙ СТАТЬИ

- Fell R., Corominas J., Bonnard Ch., Cascini L., Leroi E., Savage W.Z. Guidelines for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use planning (on behalf of the JTC-1 Joint Technical Committee on Landslides and Engineered Slopes) // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. P. 85–98.

- TC32 – Technical Committee 32 (Engineering Practice of Risk Assessment and Management) of the International Society of Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). Risk assessment – glossary of terms. 2004. URL: http://www.engmath.dal.ca/tc32/2004Glossary_Draft1.pdf.

- Terminology of disaster risk reduction. Geneva: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR). 2004. URL: http://www.unisdr.org/eng/library/lib-terminology-eng%20home.htm.

- Cruden D.M., Varnes D.J. Landslide types and processes // Landslides – investigation and mitigation: Transportation Research Board Special Report № 247 (ed. by A.T. Turner, R.L. Schuster). Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996. P. 36–75.

- Hungr O., Evans S.G., Bovis M.J., Hutchinson J.N. A review of the classification of landslides of the flow type // Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2001. Vol. VII. № 3. P. 221–238.

- Hungr O., Leroueil S., Picarelli L. Varnes classification of landslide types, an update // Eberhardt E., Froesse C., Turner A.K., Leroueil S. (eds.). Landslides and engineered slopes: protecting society through improved understanding. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2012. Vol. 1. P. 47–58.

- IAEG Commission on Landslides. Suggested nomenclature for landslides // Bull. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1990. Vol. 41. P. 13–16.

- Petley D.N. Landslides and engineered slopes: protecting society through improved understanding // Eberhardt E., Froese C., Turner A.K., Leroueil S. (eds.). Landslides and engineered slopes. London: CRC, 2012. Vol. 1. P. 3–13.

- OFAT, OFEE, OFEFP. Recommandations 1997: prise en compte des dangers dus aux mouvements de terrain dans le cadre des activites de l’amenagement du territoire. Berne: OCFIM, 1997. 42 p.

- Assessment of landslide risk in natural hillsides in масштабах Kong: Report № 191. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO), 2006. 117 p.

- AGS. Guidelines for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use management // Aust. Geomech. Australian Geomechanics Society ( AGS) Landslide Taskforce Landslide Zoning Working Group, 2007. Vol. 42. № 1. P. 13–36.

- Fell R., Corominas J., Bonnard Ch., Cascini L., Leroi E., Savage W.Z. Guidelines for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land-use planning (on behalf of the JTC-1 Joint Technical Committee on Landslides and Engineered Slopes) // Comment. Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. P. 99–111.

- Corominas J. et al. (eds.). SafeLand Deliverable D2.1: overview of landslide hazard and risk assessment practices. 2010. URL: http://www.safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Lee E.M., Jones D.K.C. Landslide risk assessment. London: Thomas Telford, 2004. 454 p.

- Glade T., Anderson M., Crozier M.J. Landslide hazard and risk. Chichester: Wiley, 2005. 802 p.

- Smith K., Petley D.N. Environmental hazards: assessing risk and reducing disaster. London: Taylor & Francis, 2008.

- Van Westen C.J., Van Asch T.W.J., Soeters R. Landslide hazard and risk zonation: why is it still so difficult? // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2005. Vol. 65. P. 167–184.

- IUGS Working Group on Landslides, Committee on Risk Assessment. Quantitative risk assessment for slopes and landslides – the state of the art // Cruden D., Fell R. (eds.). Landslide risk assessment. Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1997. P. 3–12.

- Brabb E.E., Pampeyan E.H., Bonilla M.G. Landslide susceptibility in San Mateo County, California // Misc. Field Studies, map MF-360 (scale 1:62500). Reston: US Geological Survey, 1972.

- Humbert M. Les mouvements de terrains // Principes de realisation d’une carte previsionnelle dans les Alpes // Bull. du BRGM. Sect. III. 1972. Vol. 1. P. 13–28.

- Kienholz H. Map of geomorphology and natural hazards of Grindelwald, Switzerland, scale 1:10000 // Artic Alp. Res. 1978. Vol. 10. P. 169–184.

- Brand E.W. Special lecture: landslide risk assessment in Hong Kong // Proceedings of the V International Symposium on Landslides, Lausanne, Switzerland. Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1988. Vol. 2. P. 1059–1074.

- Wong H.N., Chen Y.M., Lam K.C. Factual report on the November 1993 natural terrain landslides in three study areas on Lantau Island: GEO Report № 61. Hong Kong: Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO), 1997. 42 p.

- Hardingham A.D., Ho K.K.S., Smallwood A.R.H., Ditchfield C.S. Quantitative risk assessment of landslides – a case history from Hong Kong // Proceedings of the seminar on geotechnical risk management. Geotechnical Division, Hong Kong, 1998. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institution of Engineers, 1998. P. 145–152.

- Wong H.N., Ho K.K.S. Overview of risk of old man-made slopes and retaining walls in Hong Kong // Proceedings of the Seminar on Slope Engineering in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1998. Hong Kong: A.A. Balkema, 1998. P. 193–200.

- Ho K.K.S,, Leroi E., Roberds B. Quantitative risk assessment – application, myths and future direction // Proceedings of the International Conference on Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (GeoEng2000), Melbourne, Australia, 9–24 November 2000. Vol. 1. P. 269–312.

- Wong H.N. Landslide risk assessment for individual facilities – state of the art report // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.) Proceedings of the International Conference on Landslide Risk Management. London: Taylor & Francis, 2005. P. 237–296.

- AGS. Landslide risk management concepts and guidelines // Aust. Geomech. Australian Geomechanics Society (AGS), 2000. Vol. 35. № 1. P. 49–92.

- Cascini L. Applicability of landslide susceptibility and hazard zoning at different scales // Eng, Geol, 2008. Vol. 102. P. 164–177.

- Cascini L., Bonnard Ch., Corominas J., Jibson R., Montero-Olarte J. Landslide hazard and risk zoning for urban planning and development – state of the art report // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.). Landslide risk management. Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, 2005. P. 199–235.

- Nadim F., Kjeksta O. Assessment of global high-risk landslide disaster hotspots // Sassa K., Canuti P. (eds.). Landslides – disaster risk reduction. Berlin: Springer, 2009. P. 213–221.

- Nadim F., Kjekstad O., Peduzzi P., Herold C., Jaedicke C. Global landslide and avalanche hotspots // Landslides. 2006. Vol. 3. № 2. P. 159–174.

- Hong Y., Adler R., Huffman G. Use of satellite remote sensing data in the mapping of global landslide susceptibility // Nat. Hazards. 2007. Vol. 43. P. 245–256. J

- Fell R., Ho K.K.S., Lacasse S., Leroi E. A framework for landslide risk assessment and management // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.). Landslide risk management. London: Taylor and Francis, 2005. P. 3–26.

- Soeters R., Van Westen C.J. Slope instability recognition, analysis and zonation // Turner A.K., Schuster R.L. (eds.). Landslides investigation and mitigation: TRB Special Report 247. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996. P. 129–177.

- Leroi E., Bonnard Ch., Fell R., McInnes R. Risk assessment and management – state of the art report // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.). Landslide risk management. Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, 2005. P. 159–198.

- Van Westen C.J., Castellanos Abella E.A., Sekha L.K. Spatial data for landslide susceptibility, hazards and vulnerability assessment: an overview// Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. № 3–4. P. 112–131.

- Crosta G.B., Agliardi F., Frattini P., Sosoi R. (eds.). SafeLand Deliverable 1.1: landslide triggering mechanisms in Europe – overview and state of the art. Identification of mechanisms and triggers. 2012. URL: http://www.safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Glade T., Crozier M.J. A review of scale dependency in landslide hazard and risk analysis // Glade T., Anderson M., Crozier M.J. (eds.). Landslide hazard and risk. London: Wiley, 2005. P. 75–138.

- Turner A.K., Schuster L.R. (eds.). Landslides, investigation and mitigation: Transportation Research Board Special Report 247. Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press, 1996. 673 p.

- Springman S., Seward L., Casini F., Askerinejad A., Malet J.-P., Spickerman A., Travelletti J. (eds.). SafeLand Deliverable D1.3: analysis of the results of laboratory experiments and of monitoring in test sites for assessment of the slope response to precipitation and validation of prediction models. 2011. URL: http://www.safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Jongmans D., Garambois S. Geophysical investigation of landslides: a review // Bull. Soc. Geol. France. 2007. Vol. 178. P. 101–112.

- Corominas J., Moya J. A review of assessing landslide frequency for hazard zoning purposes // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. P. 193–213.

- Cepeda J., Colonnelli S., Meyer N.K., Kronholm K. SafeLand Deliverable D1.5: statistical and empirical models for prediction of precipitation-induced landslides. 2012. URL: http://www. safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Pitilakis K., Fotopoulou S. et al. (eds.). SafeLand Deliverable D2.5: physical vulnerability of elements at risk to landslides: methodology for evaluation, fragility curves and damage states for buildings and lifelines. 2011. URL: http://www.safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Metternicht G., Hurni L., Gogu R. Remote sensing of landslides: an analysis of the potential contribution to geo-spatial systems for hazard assessment in mountainous environments // Remote Sens. Environ. 2005. Vol. 98. № 23. P. 284–303.

- Singhroy V. Remote sensing of landslides // Glade T., Anderson M., Crozier M.J. (eds.). Landslide hazard and risk. Chichester: Wiley, 2005. P. 469–492.

- Kaab A. Photogrammetry for early recognition of high mountain hazards: new techniques and applications // Phys. Chem. Earth. Part B. 2010. Vol. 25. № 9. P. 765–770.

- Michoud C., Abellan A., Derron M.H., Jaboyedoff M. (eds.). SafeLand Deliverable D4.1: review of techniques for landslide detection, fast characterization, rapid mapping and long-term monitoring. 2010. URL: Available at http://www.safeland-fp7.eu/.

- Stumpf A., Malet J.-P. Kerle N. SafeLand Deliverable D4.3: creation and updating of landslide inventory maps, landslide deformation maps and hazard maps as inputs for QRA using remote-sensing technology. 2011. URL: http://www.safeland- fp7.eu/.

- WP/WLI. A suggested method for describing the activity of a landslide // Bull. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1993. Vol. 47. P. 53–57.

- Guzzetti F., Mondini A.S., Cardinali M., Fiorucci F., Santangelo M., Chan K.T. Landslide inventory maps: new tools for an old problem // Earth. Sci. Rev. 2012. Vol. 112. P. 42–66.

- Cardinali M. A geomorphological approach to the estimation of landslide hazards and risk in Umbria, Central Italy // Nat. Hazards Earth. Syst. Sci. 2002. Vol. 2. P. 57–72.

- Haugerud R.A., Harding D.J., Johnson S.Y., Harless J.L., Weaver C.S., Sherrod B.L. High-resolution LiDAR topography of the Puget Lowland. Washington – a bonanza for earth science // GSA Today. 2003. Vol. 13. P. 4–10.

- Ardizzone F., Cardinali M., Galli M., Guzzetti F., Reichenbach P. Identification and mapping of recent rainfall-induced landslides using elevation data collected by airborne Lidar // Nat. Hazards Earth. Syst. Sci. 2007. Vol. 7. P. 637–650.

- Van Den Eeckhaut M., Reichenbach P., Guzzetti F., Rossi M., Poesen J. Combined landslide inventory and susceptibility assessment based on different mapping units: an example from the Flemish Ardennes, Belgium // Nat. Hazards Earth. Syst. Sci. 2009. Vol. 9. № 2. P. 507–521.

- Razak K.A., Straatsma M.W., van Westen C.J., Malet J.-P., de Jong S.M. Airborne laser scanning of forested landslides characterization: terrain model quality and visualization // Geomorphology. 2011. Vol. 126. P. 186–200.

- Hervas J., Barredo J.I., Rosin P.L., Pasuto A., Mantovani F., Silvano S. Monitoring landslides from optical remotely sensed imagery: the case history of Tessina landslide, Italy // Geomorphology. 2003. Vol. 54. P. 63–75.

- Borghuis A.M., Chang K., Lee H.Y. Comparison between automated and manual mapping of typhoon-triggered landslides from SPOT-5 imagery // Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2007. Vol. 28. P. 1843–1856.

- Mondini A.C., Guzzetti F., Reichenbach P., Rossi M., Cardinali M., Ardizzone M. Semiautomatic recognition and mapping of rainfall induced shallow landslides using optical satellite images // Remote Sens. Environ. 2011. Vol. 115 . № 7 . P. 1743–1757.

- Martha T.R., Kerle N., Jetten V., van Westen C.J., Kumar K.V. Characterising spectral, spatial and morphometric properties of landslides for semi-automatic detection using object-oriented methods // Geomorphology. 2010. Vol. 116. № 1–2. P. 24–36.

- Lu P., Stumpf A., Kerle N., Casagli N. Object-oriented change detection for landslide rapid mapping // IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2011. Vol. 99. P. 701–705.

- Travelletti J., Malet J.-P., Schmittbuhl J., Toussaint R., Delacourt C., Stumpf A. A multi-temporal image correlation method to characterize landslide displacements // Ber. Geol. B.-A. 2010. Vol. 82. P. 50–57.

- Niethammer U., James M.R., Rothmund S., Travelletti J., Joswig M. UAV-based remote sensing of the Super-Sauze landslide: evaluation and results // Eng. Geol. 2012. Vol. 128. P. 2–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2011.03.012.

- Martha T.R., Kerle N., Jetten V., van Westen C.J., Vinod Kumar K. Landslide volumetric analysis using Cartosat-1-derived DEMs // Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. IEEE, 2010. Vol. 7. № 3. P. 582–586.

- Jaboyedoff M., Oppikofer T., Abellan A., Derron M.-H., Loye A., Metzger R., Pedrazzini A. Use of LIDAR in landslide investigations: a review // Nat. Hazards. 2012. Vol. 61. № 1. P. 5–28.

- Ferretti A., Prati C., Rocca F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry // Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. IEEE, 2001. Vol. 39. № 1. P. 8–20.

- Berardino P., Fornaro G., Lanari R., Sansosti E. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential interferograms // Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. IEEE, 2002. Vol. 40. № 11. P. 2375–2383.

- Farina P., Colombo D., Fumagalli A., Marks F., Moretti S. Permanent scatters for landslide investigations: outcomes from the ESA-SLAM project // Eng. Geol. 2006. Vol. 88. P. 200–217.

- Farr T.G., Rosen P.A., Caro E., Crippen R., Duren R., Hensley S., Kobrick M., Paller M., Rodriguez E., Roth L., Seal D., Shaffer S., Shimada J., Umland J., Werner M., Oskin M., Burbank D., Alsdorf D. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission // Rev. Geophys. 2007. Vol. 45. Issue RG2004. DOI:101029/2005RG000183.

- METI/NASA. ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model. Tokyo, Washington, DC: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan (METI), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 2009. URL: http://asterweb.jpl.nasa.gov/gdem.asp; http://www.gdem.ersdac.jspacesystems.or.jp.

- Nelson A., Reute H.I., Gessler P. Chapter 3: DEM production methods and sources // Hengl T., Reute H.I. (eds.) Developments in soil science, vol. 33. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2009. P. 65–85.

- Smith M.J., Pain C.F. Applications of remote sensing in geomorphology // Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2009. Vol. 33. № 4. P. 568–582.

- Aleotti P., Chowdhury R. Landslide hazard assessment: summary review and new perspectives // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 1999. Vol. 58. P. 21–44.

- Dai F.C., Lee C.F., Ngai Y.Y. Landslide risk assessment and management: an overview // Eng. Geol. 2002 . Vol. 64. P. 65–87.

- Chacon J., Irigaray C., Fernandez T., El Hamdouni R. Engineering geology maps: landslides and geographical information systems // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2006. Vol. 65. P. 341–411.

- Dobbs M.R., Culshaw M.G., Northmore K.J., Reeves H.J., Entwisle D.C. Methodology for creating national engineering geological maps of the UK // Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2012 . Vol. 45. № 3. P. 335–347.

- Xie M, Tetsuro E, Zhou G., Mitani Y. Geographic Information Systems-based three-dimensional critical slope stability analysis and landslide hazard assessment // J. Geotech Geoenviron. Eng. 2003. Vol. 129. № 12. P. 1109–1118.

- Culshaw M.G. From concept towards reality: developing the attributed 3D geological model of the shallow subsurface // Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2005. Vol. 38. P. 231–284.

- Ghosh S., Gunther A., Carranza E.J.M., van Westen C.J., Jetten V.G. Rock slope instability assessment using spatially distributed structural orientation data in Darjeeling Himalaya (India) // Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2010. Vol. 35. № 15. P. 1773–1792.

- Guimaraes R.F., Montgomery D.R., Greenberg H.M., Fernandes N.F., Trancoso Gomes R.A., de Carvalho J., Osmar A. Parameterization of soil properties for a model of topographic controls on shallow landsliding: application to Rio de Janeiro // Eng. Geol. 2003. Vol. 69. № 1–2. P. 99–108.

- Bakker M.M., Govers G., Kosmas C., Vanacker V., van Oost K., Rounsevell M. Soil erosion as a driver of land-use change // Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005. Vol. 105. № 3. P. 467–481.

- Bathurst J.C., Moretti G., El-Hames A., Begueria S., Garcia-Ruiz J.M. Modelling the impact of forest loss on shallow landslide sediment yield, Ijuez river catchment, Spanish Pyrenees // Hydrol. Earth. Syst. Sci. 2007 . Vol. 11. № 1. P. 569–583.

- Talebi A., Troch P.A., Uijlenhoet R. A steady-state analytical slope stability model for complex hillslopes // Hydrol. Process. 2008. Vol. 22. № 4. P. 546–553.

- Montgomery D.R., Dietrich W.E. A physically based model for the topographic control on shallow landsliding // Water Resour .Res. 1994. Vol. 30. № 4. P. 1153–1171.

- Santacana N., Baeza B., Corominas J., De Paz A., Marturia J. A GIS-based multivariate statistical analysis for shallow landslide susceptibility mapping in La Pobla de Lillet area (Eastern Pyrenees, Spain) // Nat. Hazards. 2003. Vol. 30. P. 281–295.

- Dietrich W.E., Reiss R., Hsu M.L., Montgomery D.R. A process-based model for colluvial soil depth and shallow landsliding using digital elevation data // Hydrol. Process. 1995. Vol. 9. P. 383–400.

- D’Odorico P. A possible bistable evolution of soil thickness //. J. Geophys. Res. 2000. Vol. 105. № B11. P. 25927–25935.

- Tsai C.C., Chen Z.S., Duh C.T., Horng F.W. Prediction of soil depth using a soil-landscape regression model: a case study on forest soils in southern Taiwan // Natl. Sci. Counc. Repub. China. Part B. Life. Sci. 2001. Vol. 25. № 1. P. 34–39.

- Van Beek L.H. Assessment of the influence of changes in landuse and climate on landslide activity in a Mediterranean environment: Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht: University of Utrecht, 2002. 363 p.

- Penizek V., Boruvka L. Soil depth prediction supported by primary terrain attributes: a comparison of methods // Plant. Soil Environ. 2006. Vol. 52. № 9. P. 424–430.

- Catani F., Segoni S., Falorni G. Accurate basin scale soil depth modelling and its impact on shallow landslides prediction. European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2007, Vienna, Austria // Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2007. Vol. 9. P. 10828.

- Hengl T., Heuvelink G.B.M., Stein A. A generic framework for spatial prediction of soil variables based on regression-kriging // Geoderma. 2004. Vol. 120. № 1–2. P. 75–93.

- Kuriakose S.L., Devkota S., Rossiter D.G., Jetten V.J. Prediction of soil depth using environmental variables in an anthropogenic landscape, a case study in the Western Ghats of Kerala, India // Catena. 2009. Vol. 79. № 1. P. 27–38.

- Gustavsson M., Kolstrup E., Seijmonsbergen A.C. A new symbol-and-GIS-based detailed geomorphological mapping system: renewal of a scientific discipline for understanding landscape development // Geomorphology. 2006. Vol. 77. № 1-2. P. 90–111.

- Pike R.J. Geomorphometry – diversity in quantitative surface analysis // Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2000. Vol. 24 . № 1. P. 1–20.

- Asselen S.V., Seijmonsbergen A.C. Expert-driven semi-automated geomorphological mapping for a mountainous area using a laser DTM // Geomorphology. 2006. Vol. 78. № 3–4. P. 309–320.

- Matthews J.A., Brunsden D., Frenzel B, Glaser B., Weiss M.M. (eds.) Rapid mass movement as a source of climatic evidence for the Holocene // Palaeoclimate Res. 1997 . Vol. 19. 444 p.

- Van Beek L.P.H., Van Asch T.W.J. Regional assessment of the effects of land-use change and landslide hazard by means of physically based modelling // Nat. Hazards. 2004. Vol. 30. № 3. P. 289–304.

- Glade T. Landslide occurrence as a response to land use change: a review of evidence from New Zealand // Catena. 2003. Vol. 51. № 3–4. P. 297–314.

- Kuriakose S.L. Physically-based dynamic modelling of the effect of land use changes on shallow landslide initiation in the Western Ghats of Kerala, India: Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht: University of Utrecht, 2010. ISBN 978-90-6164-298-5.

- Crosta G.B., Frattini P. Distributed modelling of shallow landslides triggered by intense rainfall // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2003. Vol. 3. № 1–2. P. 81–93.

- Collison A., Wade J., Griths S., Dehn M. Modelling the impact of predicted climate change on landslide frequency and magnitude in SE England // Eng. Geol. 2000. Vol. 55. P. 205–218.

- Melchiorre C., Frattini P. Modelling probability of rainfall-induced shallow landslides in a changing climate, Otta, Central Norway // Clim. Chang. 2012. Vol. 113. № 2. P. 413–436.

- Comegna L., Picarelli L., Bucchignani E., Mercogliano P. Potential effects of incoming climate changes on the behaviour of slow active landslides in clay // Landslides. 2012. Vol. 10. № 4. P. 373–391. DOI:101007/s10346-012-0339-3.

- Keefer D.K. Investigating landslides caused by earthquakes – a historical review // Surv. Geophys. 2002. Vol. 23. P. 473–510.

- Meunier P., Hovius N., Haines A.J. Regional patterns of earthquake-triggered landslides and their relation to ground motion // Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007. Vol. 34. № 20. Paper L20408.

- Gorum T., Fan X., van Westen C.J., Huang R.Q., Xu Q., Tang C., Wang G. Distribution pattern of earthquake-induced landslides triggered by the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake // Geomorphology. 2011 . Vol. 133. № 3–4. P. 152–167.

- Miles S.B., Keefer D.K. Evaluation of CAMEL – comprehensive areal model of earthquake-induced landslides // Eng. Geol. 2009. Vol. 104. P. 1–15.

- Alexander E.D. Vulnerability to landslides // Landslide risk assessment (ed. by T. Glade, M.G. Anderson, M.J. Crozier). London: Wiley, 2005. P. 175–198.

- Brenner C. Building reconstruction from images and laser scanning // Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2005. Vol. 6. № 3–4. P. 187–198.

- Chen K., McAneney J., Blong R., Leigh R., Hunter L., Magill C. Defining area at risk and its effect in catastrophe loss estimation: a dasymetric mapping approach // Appl. Geogr. 2004. Vol. 24 . P. 97–117.

- Heuvelink G.B.M. Error propagation in environmental modelling with GIS. London: Taylor & Francis, 1998. 150 p.

- Fisher P.F., Tate N.J. Causes and consequences of error in digital elevation models // Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2006. Vol. 30. P. 467–489.

- Wechsler S.P. Uncertainties associated with digital elevation models for hydrologic applications: a review // Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007. Vol. 11. P. 1481–1500.

- Ardizzone F., Cardinali M., Carrara A., Guzzetti F., Reichenbach P. Impact of mapping errors on the reliability of landslide hazard maps // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2002. Vol. 2. P. 3–14.

- Van Den Eeckhaut M., Hervas J. State of the art of national landslide databases in Europe and their potential for assessing landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk // Geomorphology. 2012. Vol. 139-140. P. 545–558.

- Carrara A., Guzzetti F., Cardinali M., Reichenbach P. Use of GIS technology in the prediction and monitoring of landslide hazard // Nat. Hazards. 1999. Vol. 20. № 2–3. P. 117–135.

- Guzzetti F., Carrara A., Cardinali M., Reichenbach P. Landslide hazard evaluation: a review of current techniques and their application in a multi-scale study // Central Italy Geomorphol. 1999. Vol. 31. № 1–4. P. 181 –216.

- Wieczorek G.F. Preparing a detailed landslide-inventory map for hazard evaluation and reduction // Bull. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1984. Vol. 21. № 3. P. 337–342.

- Crozier M.J. Multiple occurrence regional landslide events in New Zealand: hazard management issues // Landslides. 2005. Vol. 2. P. 247–256.

- Reid L.M., Page M.J. Magnitude and frequency of landsliding in a large New Zealand catchment // Geomorphology. 2003. Vol. 49. P. 71–88.

- Guzzetti F., Cardinali M., Reichenbach P., Carrara A. Comparing landslide maps: a case study in the upper Tiber River Basin, central Italy // Environ. Manage. 2000. Vol. 25. № 3. P. 247–363.

- Jaiswal P., van Westen C.J. Estimating temporal probability for landslide initiation along transportation routes based on rainfall thresholds // Geomorphology. 2009. Vol. 112. P. 96–105.

- Squarzoni C., Delacourt C., Allemand P. Nine years of spatial and temporal evolution of the La Vallette landslide observed by SAR interferometry // Eng. Geol. 2003. Vol. 68. P. 53–66.

- Colesanti C., Wasowski J. Investigating landslides with space-borne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) interferometry // Eng. Geol. 2006. Vol. 88. P. 173–199.

- Coe J.A., Michael J.A., Crovelli R.A., Savage W.A. Preliminary map showing landslides densities, mean recurrence intervals, and exceedance probabilities as determined from historic records: open-file report 00-303. Seattle: USGS, 2000.

- Bulut F., Boynukalin S., Tarhan F., Ataoglu E. Reliability of isopleth maps // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2000. Vol. 58 . P. 95–98.

- Valadao P., Gaspar J.L., Queiroz G., Ferreira T. Landslides density map of S. Miguel Island, Azores Archipelago // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2002. Vol. 2. P. 51–56.

- Lee S. Application of logistic regression model and its validation for landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS and remote sensing data // Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005. Vol. 26. № 7. P. 1477–1491.

- Yin K.J., Yan T.Z. Statistical prediction model for slope instability of metamorphosed rocks // Proc. 5th Int. Symp. on Landslides, Lausanne, Switzerland, 10–15 July 1988. Vol. 2. P. 1269–1272.

- Van Westen C.J. Application of geographic information systems to landslide hazard zonation: Ph.D. dissertation, ITC publ. № 15. Enschede: ITC, 1993. 245 p.

- Bonham-Carter G.F. Geographic information system for geoscientists: modelling with GIS. Oxford: Pergamon, 1994. 398 p.

- Suzen M.L., Doyuran V. Data driven bivariate landslide susceptibility assessment using geographical information systems: a method and application to Asarsuyu catchment // Turk. Eng. Geol. 2004. Vol. 71. P. 303–321.

- Chung C.F., Fabbri A.G. Representation of geoscience data for information integration // J. Non-Renew. Resour. 1993. Vol. 2. № 2. P. 122–139.

- Luzi L. Application of favourability modelling to zoning of landslide hazard in the Fabriano Area, Central Italy // Proc. First Joint Eur. Conf. & Exhibition on Geographical Information, The Hague, Netherlands, 26–31 March 1995. P. 398–402.

- Carrara A. Multivariate models for landslide hazard evolution // Math. Geol. 1983. Vol. 15. P. 403–427.

- Gorsevski P.V., Gessler P., Foltz R.B. Spatial prediction of landslide hazard using discriminant analysis and GIS // GIS in the Rockies 2000: Conference and Workshop: Applications for the 21st Century, Denver, CO, USA, 25–27 September 2000. URL; https://studylib.net/doc/12343493/gis-in-the-rockies-2000-conference-and-workshop.

- Ohlmacher G.C., Davis J.C. Using multiple logistic regression and GIS technology to predict landslide hazard in northeast Kansas // USA Eng. Geol. 2003. Vol. 69. № 33 . P. 331–343.

- Gorsevski P.V., Gessler P.E., Foltz R.B., Elliot W.J. Spatial prediction of landslide hazard using logistic regression and ROC analysis // Trans. GIS. 2006. Vol. 10. № 3. P. 395–415.

- Lee S., Ryu J.-H., Won J.-S., Park H.-J. Determination and application of the weights for landslide susceptibility mapping using an artificial neural network // Eng. Geol. 2004. Vol. 71 . № 3–4. P. 289–302.

- Ermini L., Catani F., Casagli N. Artificial neural networks applied to landslide susceptibility assessment // Geomorphology. 2005. Vol. 66. P. 327–343.

- Kanungo D.P., Arora M.K., Sarkar S., Gupta R.P. A comparative study of conventional, ANN black box, fuzzy and combined neural and fuzzy weighting procedures for landslide susceptibility zonation in Darjeeling Himalayas // Eng. Geol. 2006. Vol. 85. № 3–4 . P. 347–366.

- Pack R.T., Tarboton D.G., Goodwin C.N. The SINMAP approach to terrain stability mapping // 8th Congr. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol., Vancouver, Canada, 21–25 September 1998.

- Baum R.L., Savage W.Z., Godt J.W. TRIGRS - a FORTRAN program for transient rainfall infiltration and grid-based regional slope stability analysis: US Geological Survey Open-File Report 02-0424. 2002. URL: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2002/ofr-02-424/.

- Casadei M., Dietrich W.E., Mille N.L. Testing a model for predicting the timing and location of shallow landslide initiation on soil mantled landscapes // Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2003. Vol. 28. № 9. P. 925–950.

- Simoni S., Zanotti F., Bertoldi G., Rigon R. Modelling the probability of occurrence of shallow landslides and channelized debris flows using GEOtop-FS // Hydrol. Process. 2008. Vol. 22. P. 532–545.

- Jibson R.W., Harp E.L., Michael J.A. A method for producing digital probabilistic seismic landslide hazard maps: an example from the Los Angeles, California, area: open file report. Reston, USA: US Geological Survey, 1998. P. 98–113.

- Wang K.L., Lin M.I. Development of shallow seismic landslide potential map based on Newmark’s displacement: the case study of Chi-Chi earthquake, Taiwan // Environ. Earth Sci. 2010. Vol. 60. P. 775–785.

- Gunther A. SLOPEMAP: programs for automated mapping of geometrical and kinematical properties of hard rock hill slopes // Comput. Geosci. 2003. Vol. 29. P. 865–875.

- GEO-SLOPE. SLOPE/W. Calgary, Canada: GEO-SLOPE International, 2011. URL: http://www.geo-slope.com.

- Hungr O. A model for the run out analysis of rapid flow slides, debris flows and avalanches // Can. Geotech. J. 1995. Vol. 32. P. 610–623.

- Gitirana Jr.G., Santos M., Fredlund M. Three-dimensional slope stability model using finite element stress analysis // GeoCongress 2008, NewOrleans, LA, USA, 9–12 March 2008. P. 191–198.

- Hoek E., Grabinsky M.W., Diederichs M.S. Numerical modelling for underground excavations // Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. Sect. A. 1993. Vol. 100. P. A22–A30.

- Stead D., Eberhardt E., Coggan J., Benko B. Advanced numerical techniques in rock slope stability analysis: applications and limitations // LANDSLIDES – Causes, Impacts and Countermeasures, Davos, Switzerland, 17–21 June 2001. P. 615–624.

- Hart R.D. An introduction to distinct element modelling for rock engineering // Hudson J.A. (ed). Comprehensive rock engineering. Oxford: Pergamon, 1993.

- Horton P., Jaboyedoff M., Bardou E. Debris flow susceptibility mapping at a regional scale // Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on Geohazards: From Causes to Management. Quebec, Canada: Presse de l’Universite Laval, 2008. P. 399–406.

- Hungr O., Corominas J., Eberhardt E. Estimating landslide motion mechanism, travel distance and velocity: state of the art report // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.). Landslide risk management. Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema, 2005. P. 99–128.

- Hoblitt R.P., Walder J.S., Driedger C.L., Scott K.M., Pringle P.T., Vallance J.W. Volcano hazards from Mount Rainier, Washington: revised open-file report 98-428. Reston: USGS, 1998.

- Corominas J., Copons R., Vilaplana J.M., Altimir J., Amigo J. Integrated landslide susceptibility analysis and hazard assessment in the principality of Andorra // Nat Hazards. 2003. Vol. 30 . P. 421–435.

- Ayala F.J., Cubillo S., Alvarez A., Dominguez M.J., Lain L., Lain R., Ortiz G. Large scale rockfall reach susceptibility maps in La Cabrera Sierra (Madrid) performed with GIS and dynamic analysis at 1:5000 // Nat Hazards. 2003. Vol. 30. P. 325–340.

- Jaboyedoff M. Conefall v.10: a program to estimate propagation zones of rockfall, based on cone method. Lausanne: Quanterra, 2003. URL: http://www.quanterra.com.

- Jaboyedoff M., Labiouse V. Preliminary assessment of rockfall hazard based on GIS data // ISRM 2003 «Technology Roadmap for Rock Mechanics», Gauteng, South Africa, 8–12 September 2003. P. 575–578.

- Prochaska A.B., Santi P.M., Higgins J.D., Cannon S.H. Debris-flow runout predictions based on the average channel slope (ACS) // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 98. P. 29–40.

- Copons R., Vilaplana J.M. Rockfall susceptibility zoning at a large scale: from geomorphological inventory to preliminary land use planning // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. P. 142–151.

- Li T. A mathematical model for predicting the extent of a major rockfall // Z. Geomorphol. 1983. Vol. 24. P. 473–482.

- Iverson R.M., Schilling S.P., Vallance J.W. Objective delineation of lahar-inundation hazard zones // Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1998. Vol. 110 . № 8. P. 972–984.

- Rickenmann D. Empirical relationships for debris flows // Nat. Hazards. 1999. Vol. 19. P. 47–77.

- Berti M., Simoni A. Prediction of debris flow inundation areas using empirical mobility relationships // Geomorphology. 2007. Vol. 90. P. 144–161.

- Fannin R.J., Wise M.P. An empirical-statistical model for debris flow travel distance // Can. Geotech. J. 2001. Vol. 38. P. 982–994.

- Domaas U. Geometrical methods of calculating rockfall range: report 585910-1. Oslo: Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, 1994.

- Hsu K.J. Catastrophic debris stream (sturzstroms) generated by rockfalls // Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1975. Vol. 86 . P. 129–140.

- Evans S.G., Hungr O. The assessment of rockfall hazard at the base of talus slopes // Can. Geotech. J. 1993. Vol. 30. P. 620–636.

- Scheidegger A. On the prediction of the reach and velocity of catastrophic landslides // Rock Mech. 1973. Vol. 5. P. 231–236.

- Finlay P.J., Mostyn G.R., Fell R. Landslide risk assessment: prediction of travel distance // Can. Geotech. J. 1999. Vol. 36. P. 556–562.

- Copons R., Vilaplana J.M., Linares R. Rockfall travel distance analysis by using empirical models (Sola d’Andorra la Vella, Central Pyrenees) // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009. Vol. 9. P. 2107–2118.

- Hungr O., Evans S.G. Engineering evaluation of fragmental rockfall hazards // Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Landslides. Lausanne: A.A. Balkema, 1988. Vol. 1. P. 685–690.

- Rickenmann D. Runout prediction methods // Jakob M., Hungr O. (eds.). Debris-flow hazards and related phenomena. Chichester: Praxis, 2005. P. 305–324.

- Crosta G.B., Cucchiaro S., Frattini P. Validation of semi-empirical relationships for the definition of debris-flow behaviour in granular materials // Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction and Assessment, Davos, Switzerland, 2003. Rotterdam: Millpress, 2003. P. 821–831.

- Jaboyedoff M., Dudt J.P., Labiouse V. An attempt to refine rockfall hazard zoning based on the kinetic energy, frequency and fragmentation degree // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005. Vol. 5. P. 621–632.

- Scheidl C., Rickenmann D. Empirical prediction of debris-flow mobility and deposition on fans // Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2010. Vol. 35. P. 157–173.

- Piteau D.R., Clayton R. Computer rockfall model // Proc. Meeting on Rockfall Dynamics and Protective Work Effectiveness, ISMES, Bergamo, Italy, 20–21 May 1976. P. 123–125.

- Stevens W. RocFall: a tool for probabilistic analysis, design of remedial measures and prediction of rockfalls: MaSc thesis. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1998.

- Guzzetti F., Crosta G., Detti R., Agliardi F. STONE: a computer program for the three-dimensional simulation of rock-falls // Comput. Geosci. 2002. Vol. 28. P. 1081–1095.

- Guzzetti F., Malamud B.D., Turcotte D.L., Reichenbach P. Power-law correlations of landslide areas in central Italy // Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002. Vol. 195. P. 169–183.

- Pfeiffer T.J., Bowen T.D. Computer simulations of rockfalls // Bull. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1989 . Vol. 26. P. 135–146.

- Jones C.L., Higgins J.D., Andrew R.D. Colorado Rock Fall Simulation Program, version 40. Denver: Colorado Department of Transportation, Colorado Geological Survey, 2000.

- Crosta G.B., Agliardi F., Frattini P., Imposimato S. A three-dimensional hybrid numerical model for rockfall simulation // Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2004. Vol. 6. P. 04502.

- Bozzolo D., Pamini R. Simulation of rock falls down a valley side // Acta Mech. 1986. Vol. 63. P. 113–130.

- Azzoni A., La Barbera G., Zaninetti A. Analysis and prediction of rock falls using a mathematical model // Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1995. Vol. 32. P. 709–724.

- Calvetti F., Crosta G., Tatarella M. Numerical simulation of dry granular flows: from the reproduction of small-scale experiments to the prediction of rock avalanches // Rivista Italiana di Geotecnica. 2000. Vol. 2000. P. 21–38.

- Agliardi F., Crosta G.B. High resolution three-dimensional numerical modelling of rockfalls // Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2003. Vol. 40. P. 455–471.

- Dorren L.K.A., Seijmonsbergen A.C. Comparison of three GIS-based models for predicting rockfall runout zones at a regional scale // Geomorphology. 2003. Vol. 56. P. 49–64.

- Hutchinson J.N. A sliding-consolidation model for flow slides // Can. Geotech. J. 1986. Vol. 23. P. 115–126.

- Alonso E.E., Pinyol N.M. Criteria for rapid sliding I: a review of the Vaiont case // Eng. Geol. 2010. Vol. 114. P. 198–210.

- Pinyol N.M., Alonso E.E. Criteria for rapid sliding II: thermo-hydro-mechanical and scale effects in Vaiont case // Eng. Geol. 2010. Vol. 114. P. 211–227.

- Savage S.B., Hutter K. The dynamics of avalanches of granular materials from initiation to runout. Part I: Analysis // Acta Mech. 1991. Vol. 86. № 1–4 . P. 201–223.

- McDougall S., Hungr O. A model for the analysis of rapid landslide run out motion across three dimensional terrain // Can. Geotech. J. 2004. Vol. 41. P. 1084–1097.

- Pastor M., Haddad B., Sorbino G., Cuomo S., Drempetic V. A depth-integrated, coupled SPH model for flow-like landslides and related phenomena // Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 2009. Vol. 33. P. 143–172.

- Iverson R.I., Denlinger R.P. Flow of variably fluidized granular masses across three dimensional terrain. Coulomb mixture theory // J. Geophys. Res. 2001. Vol. 106. № B1. P. 537–552.

- Sosio R., Crosta G.B., Hungr O. Complete dynamic modelling calibration for the Thurwieser rock avalanche (Italian Central Alps) // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 100. P. 11–26.

- Quecedo M., Pastor M., Herreros M.I., Fernandez Merodo J.A. Numerical modelling of the propagation of fast landslides using the finite element method // Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 2004 . Vol. 59 . № 6. P. 755–794.

- Crosta G.B., Imposimato S., Roddeman D.G. Numerical modelling of entrainment/deposition in rock and debris-avalanches // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 109. № 1–2. P. 135–145.

- Pastor M., Quecedo M., Fernandez Merodo J.A., Herreros M.I., Gonzalez E., Mira P. Modelling tailing dams and mine waste dumps failures // Geotechnique. 2002. Vol. LII. № 8. P. 579–592.

- Laigle D., Coussot P. Numerical modelling of mudflows // J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE, 1997. Vol. 123. № 7. P. 617–623.

- Varnes D.J. Landslide hazard zonation: a review of principles and practice // Natural Hazard Series. UNESCO, Paris, 1984 . Vol. 3.

- Hungr O. Some methods of landslide hazard intensity mapping // Cruden D., Fell R. (eds.). Landslide risk assessment. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1997. P. 215–226.

- Guzzetti F., Galli M., Reichenbach P., Ardizzone F., Cardinali M. Landslide hazard assessment in the Collazzone area, Umbria, Central Italy // Nat. Hazards Earth. Syst. Sci. 2005. Vol. 6. P. 115–131.

- Crovelli R.A. Probabilistic models for estimation of number and cost of landslides: open file report 00-249. Reston: US Geological Survey, 2000. 23 p. URL: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2002/ofr-02-424/.

- Dussauge-Peisser C., Helmstetter A., Grasso J.-R., Hantz D., Desvarreux P., Jeannin M., Giraud A. Probabilistic approach to rock fall hazard assessment: potential of historical data analysis // Nat .Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2002 . Vol. 2. P. 15–26.

- Wong H.N., Ho K.K.S., Chan Y.C. Assessment of consequence of landslides // Cruden D., Fell R. (eds.). Landslide risk assessment. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1997. P. 111–149.

- Lee E.M., Brunsden D., Sellwood M. Quantitative risk assessment of coastal landslide problems // Bromhead E., Dixon N., Ibsen M.-L. (eds.). Landslides in Research Theory and Practice: proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Landslides. London: Thomas Telford, 2000. Vol. 2. P. 899–904.

- Budetta P.B. Risk assessment from debris flows in pyroclastic deposits along a motorway, Italy // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2002. Vol. 61. № 4. P. 293–301.

- Wu T.H., Tang W.H., Einstein H.H. Landslide hazard and risk assessment // Turner A.T., Schuster R.L. (eds.). Landslides – investigation and mitigation: Transportation Research Board Special Report № 247. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996. P. 106–118.

- Haneberg W.C. A rational probabilistic method for spatially distributed landslide hazard assessment // Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2004. Vol. X. P. 27–43.

- Wu T.H., Abdel-Latif M.A. Prediction and mapping of landslide hazard // Can. Geotech. J. 2000. Vol. 37. P. 781–795.

- Miller D.J., Sias J. Deciphering large landslides: linking hydrological groundwater and stability models through GIS // Hydrol. Process. 1998. Vol. 12. P. 923–941.

- Tacher L., Bonnard C., Laloui L., Parriaux A. Modelling the behaviour of a large landslide with respect to hydrogeological and geomechanical parameter heterogeneity // Landslides. 2005. Vol. 2. P. 3–14.

- Malet J.-P., van Asch Th.W.J., van Beek R., Maquaire O. Forecasting the behaviour of complex landslides with a spatially distributed hydrological model // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005 . Vol. 5. № 1. P. 71–85.

- Shrestha H.K., Yatabe R., Bhandary N.P. Groundwater flow modelling for effective implementation of landslide stability enhancement measures // Landslides. 2008. Vol. 5. P. 281–290. Таблица 8

- Iverson R.M. Landslide triggering by rain infiltration // Water Resour. Res. 2000. Vol. 36. P. 1897–1910.

- Baum R., Coe J.A., Godt J.W., Harp E.L., Reid M.E., Savage W.Z., Schulz W.H., Brien D.L., Chleborad A.F., McKenna J.P., Michael J.A. Regional landslide-hazard assessment for Seattle, Washington, USA // Landslides. 2005 . Vol. 2. P. 266–279.

- Godt J.W., Baum R.L., Savage W.Z., Salciarini D., Schulz W.H., Harp E.L. Transient deterministic shallow landside modelling: requirements for susceptibility and hazard assessment in a GIS framework // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. P. 214–226.

- Guzzetti F., Peruccaci S., Rossi M., Stark C. Rainfall thresholds for the initiation of landslides in central and southern Europe. Meteorol Atmos Phys // 2007. Vol. 98. № 3. P. 239–267.

- Guzzetti F., Peruccaci S., Rossi M., Stark C. The rainfall intensity-duration control of shallow landslides and debris flows: an update // Landslides. 2008. Vol. 5. P. 3–17.

- Brabb E.E. Innovative approaches to landslide hazard mapping // Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium. on Landslides, Toronto, Canada, 16–21 September 1984 . Vol. 1. P. 307–324.

- Kramer S.L. Geotechnical earthquake engineering. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall, 1996.

- Hovius N., Stark C.P., Allen P.A. Sediment flux from a mountain belt derived by landslide mapping // Geology. 1997. Vol. 25. P. 231–234.

- Pelletier J.D., Malamud B.D., Blodgett T., Turcotte D.L. Scale-invariance of soil moisture variability and its implications for the frequency-size distribution of landslides // Eng. Geol. 1997. Vol. 48. P. 255–268.

- Brardinoni F., Church M. Representing the landslide magnitude-frequency relation, Capilano River Basin, British Columbia // Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2004. Vol. 29. P. 115–124.

- Malamud B.D., Turcotte D.L., Guzzetti F., Reichenbach P. Landslide inventories and their statistical properties // Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2004. Vol. 29. P. 687–711.

- Guthrie R.H., Deadman P.J., Raymond Cabrera A., Evans S.G. Exploring the magnitude-frequency distribution: a cellular automata model for landslides // Landslides. 2008. Vol. 5. P. 151–159.

- Brunetti M.T., Guzzetti F., Rossi M. Probability distributions of landslide volumes // Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2009. Vol. 16. P. 179–188.

- Hungr O., Evans S.G., Hazzard J. Magnitude and frequency of rock falls and rock slides along the main transportation corridors of south-western British Columbia // Can. Geotech. J. 1999. Vol. 36. P. 224–238.

- Stark C.P., Hovius N. The characterization of the landslide size distributions // Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001. Vol. 28. P. 1091–1094.

- Van Den Eeckhaut M., Poesen J., Govers G., Verstraeten G., Demoulin A. Characteristics of the size distribution of recent and historical landslides in a populated hilly region // Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007. Vol. 256 . P. 588–603.

- Salciarini D., Godt J.W., Savage W.Z., Baum R.L., Conversini P. Modelling landslide recurrence in Seattle, Washington, USA // Eng. Geol. 2008. Vol. 102. № 3–4. P. 227–237.

- Guthrie R.H., Evans S.G. Analysis of landslide frequencies and characteristics in a natural system // Coast British Columbia Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2004. Vol. 29. P. 1321–1339.

- Schuster R.L., Logan R.L., Pringle P.T. Prehistoric rock avalanches in the Olympic Mountains // Wash. Sci. 1992. Vol. 258. P. 1620–1621.

- Bull W.B., King J., Kong F., Moutoux T., Philips W.M. Lichen dating of coseismic landslide hazards in alpine mountains // Geomorphology. 1994. Vol. 10. P. 253–264.

- Bull W.B,. Brandon M.T. Lichen dating of earthquake-generated regional rockfall events, Southern Alps, New Zealand // GSA Bull. 1998. Vol. 110. P. 60–84.

- Van Steijn H. Debris-flow magnitude frequency relationships for mountainous regions of Central and Northern Europe // Geomorphology. 1996. Vol. 15. P. 259–273.

- Agliardi F., Crosta G.B., Zanchi A., Ravazzi C. Onset and timing of deep-seated gravitational slope deformations in the eastern Alps, Italy // Geomorphology. 2009. Vol. 103. P. 113–129.

- Lee E.M., Meadowcroft I.C., Hall J.W., Walkden M. Coastal landslide activity: a probabilistic simulation model // Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2002. Vol. 61. P. 347–355.

- Bunce C.M., Cruden D.M., Morgenstern N.R. Assessment of the hazard from rock fall on a highway // Can. Geotech. J. 1997 . Vol. 34. P. 344–356.

- Chau K.T., Wong R.H.C., Liu J., Lee C.F. Rockfall hazard analysis for Hong Kong based on rockfall inventory // Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2003. Vol. 36. P. 383–408.

- Jakob M., Friele P. Frequency and magnitude of debris flows on Cheekye River, British Columbia // Geomorphology. 2010. Vol. 114. P. 382–395.

- Stoffel M. Magnitude-frequency relationships of debris-flows – a case study based on field surveys and tree-ring records // Geomorphology. 2010. Vol. 116. P. 67–76.

- Corominas J., Moya J. Contribution of dendrochronology to the determination of magnitude-frequency relationships for landslides // Geomorphology. 2010. Vol. 124. P. 137–149. DOI:101016/jgeomorph 201009001.

- Lopez Saez J., Corona C., Stoffel M., Schoeneich P., Berger F. Probability maps of landslide reactivation derived from tree-ring records: Pra Bellon landslide, southern French Alps // Geomorphology. 2012. Vol. 138. P. 189–202.

- Van Dine D.F., Rodman R.F., Jordan P., Dupas J. Kuskonook Creek, an example of a debris flow analysis // Landslides. 2005. Vol. 2. № 4. P. 257–265. DOI:101007/s10346-005-0017.

- Jakob M. Morphometric and geotechnical controls of debris-flow frequency and magnitude in southwestern British Columbia: Ph.D. thesis. Vancouver: Geography Department, the University of British Columbia, 1996.

- Jakob M. The fallacy of frequency. Statistical techniques for debris flow frequency magnitude analysis // Proceedings of the International Landslide Conference, Banff, Canada, 2–8 June 2012. Vol. 1 . P. 741–750.

- Corominas J., Copons R., Moya J., Vilaplana J.M., Altimir J., Amigo J. Quantitative assessment of the residual risk in a rockfall protected area // Landslides. 2005. Vol. 2. P. 343–357.

- Agliardi F., Crosta G.B., Frattini P. Integrating rockfall risk assessment and countermeasure design by 3D modelling techniques // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009. Vol. 9. P. 1059–1073.

- Frattini P., Crosta G.B., Sosio R. Approaches for defining thresholds and return periods for rainfall-triggered shallow landslides // Hydrol. Process. 2009 . Vol. 23. № 10. P. 1444–1460.

- Crosta G.B., Agliardi F. A methodology for physically-based rockfall hazard assessment // Nat. Hazards. Earth Syst. Sci. 2003. Vol. 3. P. 407–422.

- Hungr O., McDougall S., Wise M., Cullen M. Magnitude-frequency relationships of debris flows and debris avalanches in relation to slope relief // Geomorphology. 2008. Vol. 96. P. 355–365.

- Jakob M. A size classification for debris flows // Eng. Geol. 2005. Vol. 79. P. 151–161.

- Bovolin V., Taglialatela L. Proceedings Scritti in onore di Lucio Taglialatela: CNR-GNDCI publ. № 2811. Perugia: CNR-GNDCI, 2002. P. 429–437.

- Calvo B., Savi F. A real-world application of Monte Carlo procedure for debris flow risk assessment // Comput. Geosci. 2009 . Vol. 35. № 5. P. 967–977.

- Borter P. Risikoanalyse bei gravitativen Naturgefahren. Bern: Bundesamt fur Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft, 1999.

- Fuchs S., Heiss K., Hubl J. Towards an empirical vulnerability function for use in debris flow risk assessment // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007. Vol. 7. P. 495–506.

- Saygili G., Rathje E.M. Probabilistically based seismic landslide hazard maps: an application in Southern California // Eng. Geol. 2009. Vol. 109. P. 183–194.

- Mansour M.F., Morgenstern N.I., Martin C.D. Expected damage from displacement of slow-moving slides // Landslides. 2011 . Vol. 8. № 1. P. 117–131.

- Archetti R., Lamberti A. Assessment of risk due to debris flow events // Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003. Vol. 4. № 3. P. 115–125.

- Friele P., Jakob M., Clague J. Hazard and risk from large landslides from Mount Meager Volcano, British Columbia, Canada // Georisk. 2008. Vol. 2. № 1. P. 48–64.

- Jakob M., Stein D., Ulmi M. Vulnerability of buildings to debris flow impact // Nat. Hazards. 2012. Vol. 60. P. 241–261.

- Gentile F., Bisantino T., Trisorio Liuzzi G. Debris-flow risk analysis in south Gargano watersheds (Southern Italy) // Nat. Hazards. 2008. Vol. 44. P. 1–17.

- Frattini P., Crosta G.B., Lari S., Agliardi F. Probabilistic rockfall hazard analysis (PRHA) // Eberhardt E., Froese C., Turner A.K., Leroueil S. (eds.). Landslides and engineered slopes: protecting society through improved understanding. London: Taylor & Francis, 2012. P. 1145–1151.

- Michoud C., Derron M.H., Hortin P., Jaboyedoff M., Baillifard F.J., Loye A., Nicolet P., Pedrazzini A., Queyrel A. Rockfall hazard and risk assessments along roads at a regional scale: example in Swiss Alps // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012. Vol. 12. P. 615–629.

- Jaiswal P., van Westen C.J., Jetten V. Quantitative assessment of direct and indirect landslide risk along transportation lines in southern India // Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010. Vol. 10. № 6. P. 1253–1267.

- Roberds W. Estimating temporal and spatial variability and vulnerability // Hungr O., Fell R., Couture R., Eberhardt E. (eds.). Landslide risk management. London: Taylor & Francis, 2005. P. 129–158.

- Van Dine D.F., Rodman R.F., Jordan P., Dupas J. Kuskonook Creek, an example of a debris flow analysis // Landslides.2005. Vol. 2. № 4. P. 257–265. DOI:101007/s10346-005-0017.

- Keefer D.K. Landslides caused by earthquakes // Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1984. Vol. 95. № 4. P. 406–421.